There’s a reason that online multiplayer games like Clash of Clans are so popular. When we leverage that engagement in the class, serious learning can come out of play. (Image via Supercell)

When my son was 5 years old he loved the game Clash of Clans.

If you’ve never played this online multiplayer game, the premise is this: You create an army of warriors and a village for them to live in. Then you find armies of other users of the game and you do battle against them. You earn gold and elixir to create more things in your village and more troops.

There are many reasons for its wild success, which has made it one of the most popular games for iOS and Android and earns the company $2.4 million every day (yes, every DAY).

One reason: you get to build your village how you want. You buy the upgrades. You put them in place strategically. It’s all up to you.

But you can’t do everything all at once. You have to earn gold and elixir to do most everything in the game, and they’re finite resources. You either have to wait until your workers have harvested more gold and elixir, or you can pull out your credit card and buy more. (And when I say “pull out your credit card,” I don’t mean in the realm of the game. This is real money in the real world.)

For a time, several of my students were excited about this game, too. They had split into two factions and warred against each other at home, then came to school to swap battle stories.

One day, it hit me: I could leverage Clash of Clans’s success in my classroom. If it engaged my students and the world, certainly its premise could engage my students in my Spanish classes.

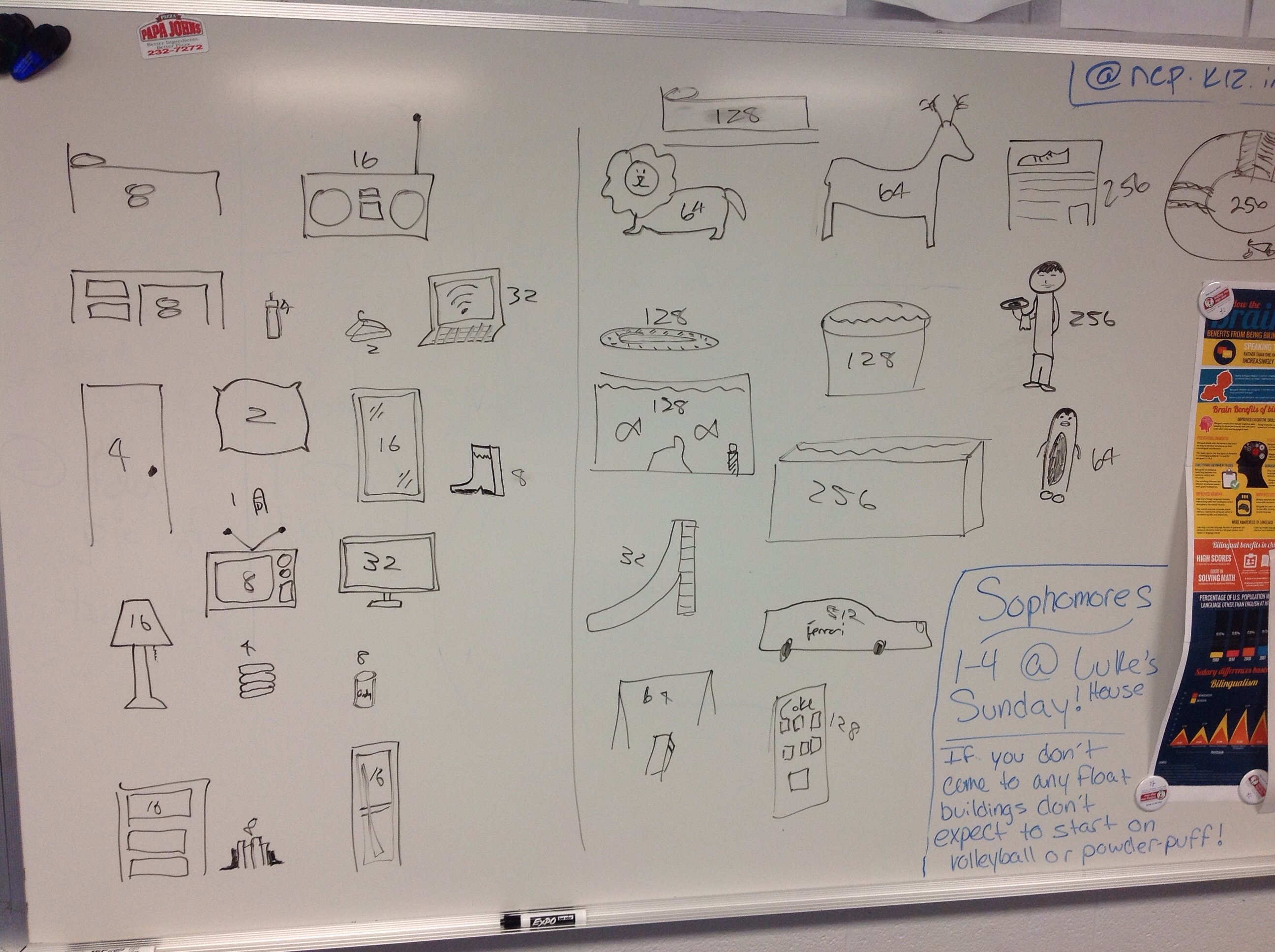

Students ponder what new items to add to their bedrooms in “Ultimate Bedroom Makeover.” (Photo via Matt Miller)

So the “Ultimate Bedroom Makeover” game was born. My game wasn’t about troops and villages. It was about lamps and beds and TVs. Teams of students earned points by answering questions and spent them by adding new features to the team’s bedroom. Students told me what items should be available for purchase and I drew them on the board.

Items ranged from one point (a stick of deodorant) to 512 points (a Ferrari, and a poorly drawn one at that!). Then we got into a rapid-fire series of questions and the student groups started earning points.

Each successive correct answer doubled the point value of the next question (i.e. the first question was worth 1 point, the next was worth 2, the next was worth 4, etc.). At any time, the teams could bank their points so they could keep them or risk losing them by trying for the next highest point value. It was reminiscent of the TV game show “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?”

Students came up with the items that could be purchased with points from answering questions. (Photo via Matt Miller)

It worked. The teams were motivated to get answers correct. They were creative in how they spent their points and decorated their bedrooms. They were engaged in the activity and engaged in the content.

In the end, I arbitrarily decided which room was the best to determine a winner. In the future, though, I think I might let the students vote (the exception: you can’t vote for your own room).

I can see possibilities for this going beyond a single day review game. Students could keep the same teams and build rooms throughout the year until they created a house at the end, which could come with a bigger prize. They could even do things throughout the year — not on review game day — to earn additional points.

This idea of gamifying class has taken the education world by storm. One teacher, Michael Matera, has assigned “XP” — experience points, a common currency in video games — to everything in his classroom to keep his junior high students engaged.

Some other resources about gamifying the classroom:

- Vicki Davis and her students summarize what makes games in the classroom succeed.

- Formal research examines the benefits and drawbacks of gamifying the classroom.

This school year, I’ve been motivated to increase engagement with my students. I want to create classroom experiences that they’ll remember so that they’ll take things they’ve learned in my class with them in their lives. This was one little step in that bigger picture.

What is your take on gamifying the classroom? Is its engagement factor worth using? How have you used gamification in your class, or how could you see it working? Please tell us in a comment below!

(For notifications of new Ditch That Textbook content and helpful links, “like” Ditch That Textbook on Facebook and follow @jmattmiller on Twitter!)

Interested in having Matt present at your event or school? Contact him by e-mail!

hola bruno r y adrian s

[…] There’s a reason that online multiplayer games like Clash of Clans are so popular. When we leverage that engagement in the class, serious learning can come out of […]

[…] Indiana-based teacher and author Matt Miller (Ditch That Textbook) wrote about how infusing principles of video gaming into his classroom changed the way his students looked at (and engaged with) something as basic as […]

Consider looking at Classcraft.com–it’s a Canadian site that has planned out some of the gamification stuff. I’m using it for the 2nd year with my students, but this year I added a “Skyrim” style map that they must conquer.

I find it interesting that you mntieon the possibility of negative effects on kids who find themselves on the lower halves of the leaderboards. The interesting thing about gamification in education is that a lot of experts think that gamification actually has the greatest effect on kids on the lower half of classes. On the case I mntieoned in class, Lee Sheldon’s game design class, the reversal of traditional grading systems gave students a greater sense of agency, or the idea that their grades were in their own hands, rather than in the hands of outside forces. For underperformers, it’s that greater sense of agency, rather than a desire to be on top, that improves performance. I don’t know if being on the lower half of a leaderboard or even leaderboards themselves (correlation not causation) would have much of an effect without other aspects and mechanics, especially since there are already schools with rankings by class. I don’t come from a school that does rankings, though, so I don’t know much about that subject.