Many well-meaning teachers have been giving bad advice when it comes to studying. Cognitive science gives us a better option that will benefit everyone. (Public domain image via Pixabay.com)

What if you didn’t have to spend so much time re-teaching material to your students?

What if that material was securely saved in their minds, ready for recall whenever necessary? And they could apply that knowledge to whatever they were learning at the moment?

Even though there’s no magic bullet to make students remember everything vividly and perfectly, there is a practice that’s scientifically proven. It can help students remember and recall important facts and ideas on tests and in real life.

Sadly, many teachers all over the world aren’t using it.

Sadly, many of them are giving bad advice instead and don’t even know it.

How do we coach students to prepare for a quiz or a test? We tell them to study. To re-read. To go back over the material.

Well-meaning teachers tell students to do this all the time. However, science tells us it’s one of the least effective ways to prepare.

A much better way is something called “retrieval.” Here’s how it works:

It seems so simple, but it can have profound results.

Fellow educator Alice Keeler and I are working on a book called Ditch That Homework, which suggests strategies teachers can use to minimize or eliminate their need for homework. Retrieval is one strategy that we recommend, and the scientific studies behind it are interesting.

A study done at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana, tested two methods for studying and remembering material.

The first was elaboration — memorization through repetition, like the “read and re-read” strategy. Students read and also created a concept map to remember new ideas.

The second was retrieval — pulling information from your memory. Students recalled information on a “free recall test” while they studied.

They were both given the same amount of study time.

The results: Better scores and a 50-percent improvement in long-term retention for students using retrieval. A follow-up experiment gave the elaboration strategy a huge advantage and retrieval still outperformed.

What’s the perfect balance between reading and retrieving? In the book Make It Stick, the authors describe a study that showed a sweet spot in the balance of studying and retrieval.

That sweet spot was 60 percent. We would expect that means 60 percent of study time reading and studying, and 40 percent of study time retrieving information from memory. Right?

Think again. The study suggested 60 percent retrieving/recalling information from memory and 40 percent reading/studying.

If retrieval is a scientifically-proven effective approach to learning, why isn’t its use widespread in schools? Why aren’t education students taught its benefits in college?

Maybe teachers just aren’t aware of it. Or maybe they don’t believe it will work.

It’s unintuitive. It seems too good to be true — or too easy to be truly effective.

In the study above, the researchers also asked participants which approach they thought would be more effective. Their answers weren’t based on science — just on their own intuition.

Half expected elaboration to work best. Only a quarter said retrieval. The other quarter said they’d be equally effective.

Only 25 percent of those participants thought retrieval would give them an advantage. Even if it doesn’t seem like it should work, the science and the results should be enough to make us consider its effectiveness.

One way to implement retrieval is to simply encourage it as a study strategy to students. Ask students to stop reading their books or notes and start pulling information from their brains. Have them retrieve what they’ve learned quietly in their minds, verbally out loud or written on paper.

It makes sense — if we’re going to retrieve information from our brains during a test, why wouldn’t we rehearse that way beforehand?

Cognitive scientist Pooja K. Agarwal, who was once a classroom teacher, has studied retrieval practice and makes recommendations for teachers. Her advice can be found at RetrievalPractice.org, where she offers a free digital guide for implementing retrieval effectively.

Some of her suggestions:

Who should use retrieval practice? Agarwal says all grade levels, all subject areas — all students — benefit.

Imagine student retention improving, of less need for re-teaching.

That scenario can become more and more of a reality if we’re willing to ditch that old “textbook” mindset of studying and try a new one.

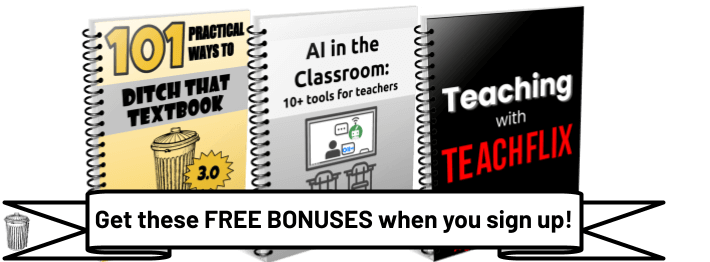

For notifications of new Ditch That Textbook content and helpful links:

Interested in having Matt present at your event or school? Contact him by e-mail!

Matt is scheduled to present at the following upcoming events:

[getnoticed-event-table scope=”upcoming” max=”15″ expanding=”false”]

Session expired

Please log in again. The login page will open in a new tab. After logging in you can close it and return to this page.

Completely agree.

What I have come to believe is that we need retrieval — pulling information from students memory.

Thank you for helpful and practical article.

I love this! Retrieval makes sense. In my math classroom – we put so much focus on the common core practice standards. We call them “Think Like a Mathematician” (TLM) standards. Every time they finish solving a problem with their teammates, they work on explaining their solution with their thinking, steps, TLM practice standard, etc. Would you consider this retrieval? I think it makes them stop and think about what they’re doing as they go, and at least it makes them “retrieve” their steps once their finished. Interesting concept!

Yes! If it isn’t retrieval, it’s definitely metacognition, and both are so important. Great work!